| Nation Overview | Strategic Overview | CtW Information | History |

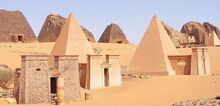

View of the Nubian Pyramids of Meroë, three of them reconstructed. Built some 800 years after the Egyptian Pyramids, far from Egypt, far after the rule of the last Pharaohs; the Nubian Kingdoms stood strong as the last remnant of sovereign native culture in the Nile Valley for centuries.

Nubia is a region along the Nile River with a long and rich history of 4000 years, at the very least, encompassing most of modern-day Sudan and Southern Egypt. Since ancient times the Egyptians regarded Nubia, known to them as "Ta-Seti", "Land of the Bow", as their southern enemies; the defiant foreigners who defended the southern lands from Egyptian expansion, on most occasions raiding accross the frontier, at times recognizing nominal Egyptian suzerainity, and other times even managing to conquer Egypt altogether and establishing Nubian Pharaohs. This long history of wars, both offensive and defensive on both sides, meant that something as "exact" borders between Egypt and Nubia weren't really there. The traditional frontier was between the First and Second Cataracts of the Nile, near present-day Aswan, where both nations clashed for most of history. But at times the Egyptians expanded far beyond that border, and built cities and monuments farther south (For instance, Abu Simbel), both to press on the Nubians and claim sovereignity over them. Not to mention that cultural and demographic exchange between the two regions is something that always ocurred. "Nubians" and "Egyptians" were travelling to each other's lands before Egypt or Nubia even existed as political entities.

In contrast to the better-known African civilizations of Egypt and Ethiopia, knowledge of the Nubians has been victim of curtailing. Firstly, by the dearth of physical evidence; the remoteness of Nubian lands and ongoing conflict has for most purposes made difficult an attempt to lift the veil of the past. And secondly, the wide attention that Egyptology has received throughout the centuries has caused a "pro-Egyptian" view of the region, regarding the lands to the south as a secondary area under Egyptian influence instead of a proper culture by its own merits; a vision not commonly challenged or deeply analyzed until recent times. And so most of the sources are essentially the writings of northern rivals: from ancient Egyptian border wars to Muslim incursions, Nubia has always been seen as the enduring realm of the foreign.

The First Children of the Nile

In a similar fashion to that of Egypt, Nubia has been traditionally divided into Upper (Southern) and Lower (Northern) portions, indicating the northwards flow of the Nile River, and the greater altitude of the land upstream. Lower Nubia stands between the First and Second Cataracts of the Nile, in modern Southern Egypt and Northern Sudan, while Upper Nubia extends from the Second to the Sixth Cataract in modern central Sudan. Both lands were settled since early times. By the 5th millennium BCE, the people who inhabited what is now called Nubia participated in the Neolithic revolution. Saharan rock reliefs depict scenes that have been thought to be suggestive of a cattle cult, typical of those seen throughout parts of Eastern Africa and the Nile Valley even to this day. Megaliths discovered at Nabta Playa are early examples of what seems to be one of the world's first astronomical devices, predating Stonehenge by almost 2,000 years. This complexity as observed at Nabta Playa, and as expressed by different levels of authority within the society there, likely formed the basis for the structure of both the Neolithic society at Nabta and the Old Kingdom of Egypt.

Around 3500 BC, second "Nubian" culture, termed the "A-Group", arose. It was a contemporary of, and ethnically and culturally very similar to, the polities in predynastic Naqada of Upper Egypt. The "A-Group" people were engaged in trade with the Egyptians. This trade is testified archaeologically by large amounts of Egyptian commodities deposited in the graves of the "A-Group" people. The imports consisted of gold objects, copper tools, faience amulets and beads, seals, slate palettes, stone vessels, and a variety of pots. Around 3300 BCE, there is evidence, shown by finds at Qustul, Lower Nubia, of a unified kingdom that maintained substantial interactions, both cultural and genetic, with the culture of Naqadan Upper Egypt. The Nubian culture may have even contributed to the unification of the Nile Valley. It was also at Qustul that the earliest known depiction of the white crown of "Upper Egypt" has been found, on a ceremonial incense burner found in a cemetery.

The Nile At War

For much of antiquity, the region south of the 1st cataract of the Nile was called "Kush." The name is known from ancient Egyptian, classical, and biblical texts. Whether it reflects an indigenous term is not known. In referring to the Kushites, the Egyptians often said “vile Kush” because they were in a foreign country. For the Kushites, their relationship with Egypt was often a love-hate affair. They hated being under Egypt’s thumb, yet at the same time they adopted many Egyptian cultural concepts. For example, when the Egyptians went south, they would build temples to Amun. Eventually, the Kushites (Nubians) were also worshipping at these temples. When the Egyptian empire went into decline, Kushite kings would eventually come to rule Egypt and maintain Egypt's cultural identity. by 2800 B.C. lower Nubia fell under the control of Egypt, because of the gold mines located in the area. With increasing aggression from Egypt, a united Nubian Kingdom emerged with its capitol at the city of Kerma by 2500 B.C. It was during the late "Old Kingdom" period of Egypt history that a nomadic tribe that lived in Nubian territory was first recruited by the Egyptians as mercenaries into the Egyptian army and as a desert police force due to their military skills. But as Egyptian power weakened during the "First Intermediate" Period, people known as the "C-Group" culture (descendants of the A-Group) begin to resettle Lower Nubia.

A Unified Nubia: Kingdom Of Kerma

Spurred by threats from the south, Egypt’s New Kingdom pharaohs mounted military campaigns against Nubia, and by the Reign of Thutmose III (1479–1425 BC) Egyptians controlled Nubia to the 4th cataract. An Egyptian govenor administered the country called Kush and ensured the flow of Nubian gold to Egypt, along with other prized goods such as animal skins, ivory, and ebony as well as dates, cattle, and horses.

Despite being required to send many rich resources to Egypt, Nubia prospered during this period. Many Egyptians settled in Nubia, and Nubians moved north to Egypt. Egyptians build large temples and monuments in Nubia Egyptian pharoahs constructed temples throughout Nubia to honor Egyptian deities, gods unique to Nubia, and themselves as divinities.

The most important religious site in Nubia was dedicated to the Egyptian state god Amun. It was located at the foot of a sacred mountain (modern Gebel Barkal) at the frontier settlement of Napata near the 3rd cataract. Started by Thutmose III, this temple complex was enlarged by later pharaohs. New Kingdom Egyptian pharaohs conducted many campaigns to bring Nubia under Egyptian control. By the time of Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC) Nubia had been a colony for two hundred years, but its conquest was recalled in a painting from the temple Ramesses II built at Beit el-Wali in Northern Nubia. It was the subject of epigraphic work by the Oriental Insitute during the Nubian salvage caokimpaign of the 1960s. The epigraphic drawing of the painting is shown below.

The Other Land Of The Pyramids: Kingdom Of Kush

As often the case, the tied of history switches sides. In 1070 B.C., Upper Nubia would again become independent and by 760 B.C. all of Nubia would be united under King Kashta, from the first to the sixth cataract. This period was known as the Napata period, as the Nubians took to burying their Kings at the former Egyptian stronghold, taking it as their own. The Nubians would go even further, in 743 B.C., the Kushite King Piye invades Upper Egypt seizing control of it from the Egyptians. His successor Shabaqo would establish the 25th Pharaonic dynasty by uniting both Upper and Lower Egypt under Kushite rule, establishing the Empire of Kush. However, about a hundred years after its establishment, under Pharaoh Taharqo the Empire intervened in the area of modern Syria in opposition to the Assyrians. The Assyrians responded by invading Egypt and driving the Nubian king out of Egypt and forcing him to withdraw back to their homeland and return the dynasty to Napata. In 590 B.C., they would again have to move their capitol, when an Egyptian army sacked Napata. This time, to the city of Meroe situated near the sixth cataract, well away from northern aggression. Napata would still remain an important religious center for the Nubians but the royal necropolis was also moved to Meroe ushering in the Meroitic period of Nubian history. For several centuries thereafter, the Kushite Kingdom centered in Meroe developed independently of Egypt. While still preserving the Pharaonic traditions like the raising of stelae to record the achievements of their reigns and erecting pyramids to contain their King's tombs.

The Children Of The Nile Live On: Kingdom of Meroë

The city of Meroe was ideally situation at the convergence of a network of trade routes that ran along the White and Blue Niles. Meroe became East Africa's most important center of trade. The civilization thrived on trade with Egypt and the Greco-Roman World, in addition to Arab and Indian traders along the Red Sea. The Kushite Kings even managed to create an irrigation system that was capable of supporting a higher population density during this period then had been or would be possible in the future. The Nubians also developed a new Meroitic script based on the Egyptian writing system to better represent the indigenous spoken language of its people. Despite mostly peaceful relations with it neighbors, Nubian ambitions in Upper Egypt provoked the Roman Army in 23 B.C. to move south against them razing Napata to the ground. The Romans however abandoned the area as being unfit for Roman colonization. During the 2nd century A.D., a tribe known as the Nobatae that occupied the Nile's west bank in Northern Kush integrated themselves first as mercenaries then as a military aristocracy into the Meroitic Kingdom. Introducing Camelry as a weapon of war into the Nubian culture. However the fortunes of the Kushite Kingdom would come to an end in the 4th century A.D., when it was overwhelmed by the kingdom of Aksum that had developed in Abyssinia (or modern Ethiopia) to the southeast.

A Force To Be Reckoned: Christian Kingdom of Nubia

Officially, it is accepted that the Nubian people converted to Christianity in the year 540 with joint declarations by the rulers of the Nubians. Subsequently, the influence of Christianity would be seen in the buildings and culture. Christian religious books were translated into the Nubian language. The Nubians also wrote down their laws, letters and other documents. These writings are a precious record of this culture and language. It is also believed that because of this early conversion to Christianity, the Nubians were among the first people to spread the faith in Europe.

However, it was not surprising as Egypt then Abyssinia had both been converted to Christianity in the previous century by the Byzantines. The Nubians as they seemed to have always done in the past adopted Egyptian traditions accepting religion suzerainty from the Coptic Church based in Alexandria. This period saw a resurgence of the cultural and ideological connections between the Mediterranean World with the Nubians. The Greek language infiltrated Nubian society through religious teachings, and remained strong even until the 12th century CE.

The Fall Of Nubia: Islamization of Sudan

The Nubian rulers grew weaker as time passed and in the 15th century the kingdom finally dissolved. The Arabs took over the region bringing with them their own culture, and it's from this point that the term "Nubia" falls out of parlance and is instead replaced with "Sudan", derived from the Arabic aswad/s-w-d, meaning "black" viz "land of black people". However, in some areas of southern Egypt and northern Sudan the Nubian people kept their culture and traditions until the present day,

Once Muslims began to dominate Egypt, Nubia's connection as well as to the rest of the Christian World was lost. The Arabs invaders that had taken control of Egypt tried to take the Nubian Kingdoms by force but was repelled, not once but twice, in 642 A.D. and again in 652 A.D. This forced the successor states to reunite. The Arabs then turn to seek peaceful relations with the Nubians to facilitate trade between the two cultures. The Christian Nubian Kingdoms reached its height in the 9th and 10th century. However, over the next 1000 years the Islamic influences brought about by Arab merchants as they began to establish trade posts and intermarried into the population gradually turned the Nubians into a majority Islamic, Arabic speaking nation. The turning point was in the 13th century A.D., when the Mamelukes from Egypt intervened in a dynastic dispute within the Nubian monarchy forcing the Northern Kingdoms of Nubia to be satellite state to Egypt.

By the 15th century A.D. as the Christian church declined in influence, a period of political instability and fragmentation ensued. The resulting chaos led to an increase in raids by slave traders. The population began to convert to Islam in even greater number in order to seek the protection of Arab protectors. The Islamization of Nubia also created the beginnings of a division between North and South. Islam encouraged political unity, economic growth and education but these efforts were largely restricted to the urban and commercial centers in the North where the most of the Arabs controlled. In 1517 A.D. the Turks took control of Egypt, forcing the Mameluke to flee south into Nubia. The Mamelukes eventually made peace with the Ottomans, agreeing to be ruled under the Kashif system under the Pasha in Cairo. However the Mamelukes remained in Northern Nubia pillaging the land for its wealth and people, in the form of taxes and slaves as they jockeyed for title and territory for themselves. Meanwhile, in Southern Nubia, the Funj Empire supplanted the remnants of the Christian Kingdoms. The Funj consisted of a confederation of Sultanates and dependent chiefdoms, based on military rule and a slave trade economy. The Funj State however created stability in the region by interposing a strong military bloc between the various powers that surrounded it.

Modern Nubians And Present Day

This state of affairs continued for almost 300 years until the 18th century. By then it became clear that the Mamelukes were the real power in Egypt, but then it it was the time when Napoleon decided to invade Egypt, and finally broke the power of the Mamelukes. However, Britain being an adversary of the French, decided to intervene on behalf of the Ottoman Turks to regain control of their wayward province. The Ottomans also sent Muhammad Ali as Pasha (provincial governor) to restore Ottoman interests in the area, for which he did exceedingly well.

Removing the Mameluke power structure from Egypt, but this time also removing any of them that had fled to Sudan. He also forced the last of the Funj Sultanates to surrender their authority when they refused to give up the Mamelukes that had fled into their domain. This period (1821 A.D. to 1885 A.D.) was known as the Turkiyah or Turkish Regime, but for Sudan it was no better then the previous state of affairs. They were again subject to parasitic taxation, and the slave trade became an official state run enterprise. The slave trade further exacerbated the North-South tension, as it was often the Muslim Northern Sudanese preying upon the non-Muslim South. Not only was the cost high for the Sudanese in human lives, but the disruption to economic and social enterprises especially in the South were debilitating.

It wasn't until the British who had by then ceased the practice of slavery themselves, pressured the Ottomans to end the practice in Egypt and severed it from official government sponsorship. In 1869CE the British set out to annex all territory from Equatorial Africa to the White Nile's basin and to suppress the slave trade by force. Charles George Gordon, a British officer whose other claim to fame was as the General who put down the Boxer Rebellion in China, was given this task. He accomplished this task quite successfully, being appointed Governor General of Sudan in 1877CE. However, the respite in the slave trade was only a short one, as Gordon resigned as Governor only 3 years after his appointment. The illegal slave trade was again running rampant, unemployed soldiers was wreaking havoc in the land, and government taxation policies were heavy and arbitrary. In 1881, a religious leader named Muhammad ibn Abdalla proclaimed himself the Mahdi, or the "expected one," and began a religious crusade to unify the tribes in western and central Sudan. His followers took on the name "Ansars" (the followers) which they continue to use today and are associated with the single largest political grouping, the Umma Party, led by a descendant of the Mahdi, Sadiq al Mahdi. Taking advantage of dissatisfaction resulting from Ottoman-Egyptian exploitation and maladministration, the Mahdi led a nationalist revolt culminating in the fall of Khartoum in 1885. The Mahdi died shortly thereafter, but his state survived until overwhelmed by an invading Anglo-Egyptian force under Lord Kitchener in 1898. While nominally administered jointly by Egypt and Britain, Britain exercised control, formulated policies, and supplied most of the top administrators.

Independence and Civil War

Until 1969, there was a succession of governments that proved unable either to agree on a permanent constitution or to cope with problems of factionalism, economic stagnation, and ethnic dissidence. These regimes were dominated by "Arab" Muslims who asserted their Arab-Islamic agenda and refused any kind of self-determination for southern Sudan. Since independence, protracted conflict rooted in ethnoreligious (and possibly socioeconomic) differences retarded Sudan's economic and political development and forced massive internal displacement of its people.

In February 1953, the United Kingdom and Egypt concluded an agreement providing for Sudanese self-government and self-determination. The transitional period toward independence began with the inauguration of the first parliament in 1954. With the consent of the British and Egyptian Governments, Sudan achieved independence on January 1, 1956, under a provisional constitution. This constitution was silent on two crucial issues for southern leaders--the secular or Islamic character of the state and its federal or unitary structure. Northerners, who have traditionally controlled the country, have sought to unify it along the lines of Arabism and Islam despite the opposition of non-Muslims, southerners, and marginalized peoples in the west and east.

The Arab-led Khartoum government reneged on promises to southerners to create a federal system, which led to a mutiny by southern army officers that launched 17 years of civil war (1955-72). In 1958, General Ibrahim Abboud seized power and pursued a policy of Arabization and Islamicization in the south that strengthened southern opposition. General Abboud was overthrown in 1964 and a civilian caretaker government assumed control. Southern leaders eventually divided into two factions, those who advocated a federal solution and those who argued for self-determination, a euphemism for secession since it was assumed the south would vote for independence if given the choice.

Then in May 1969, a group of communist and socialist officers led by Colonel Gaafar Muhammad Nimeiri, seized power. A month after coming to power, Nimeiri proclaimed socialism (instead of Islamism) for the country and outlined a policy of granting autonomy to the south. Nimeiri in turn was the target of a coup attempt by communist members of the government. It failed and Nimeiri ordered a massive purge of communists. This alienated the Soviet Union, which withdrew its support. Already lacking support from the Muslim parties he had chased from power, Nimeiri could no longer count on the communist faction. Having alienated the right and the left, Nimeiri turned to the south as a way of expanding his limited powerbase. He pursued peace initiatives with Sudan's hostile neighbors, Ethiopia and Uganda, signing agreements that committed each signatory to withdraw support for the other's rebel movements. He then initiated negotiations with the southern rebels and signed an agreement in Addis Ababa in 1972 that granted a measure of autonomy to the south. Southern support helped him put down two coup attempts, one initiated by officers from the western regions of Darfur and Kordofan who wanted for their region the same privileges granted to the south. However, the Addis Ababa Agreement had no support from either the secularist or Islamic northern parties. Nimeiri concluded that their lack of support was more threatening to his regime than lack of support from the south so he announced a policy of national reconciliation with all the religious opposition forces. These parties did not feel bound to observe an agreement they perceived as an obstacle to furthering an Islamist state. Oil was literallly added to the fire with the discover of oilfields in the south. Northern pressure built to abrogate those provisions of the peace treaty granting financial autonomy to the south. Ultimately in 1983, Nimeiri abolished the southern region, declared Arabic the official language of the south (instead of English) and transferred control of southern armed forces to the central government. This was effectively a unilateral abrogation of the 1972 peace treaty.

The second Sudan civil war effectively began in January 1983 when southern soldiers mutinied rather than follow orders transferring them to the north. Attempts by President Nimeirito impose Shari'a law only exacerbated the crisis, and even alienated substantial elements of Sudanese Muslim society and so Nimeiri was overthrown by a popular uprising in Khartoum in 1985. Another military man, Suwar al-Dahab headed the transitional government. One of its first acts was to suspend the 1983 constitution and disband Nimeiri's Sudan Socialist Union. Elections in 1986 eventually marked a return to and a civilian government, along with peace negotiations with the south. However, any proposal to exempt the south from Islamic law was unacceptable to those who supported Arab supremacy. Once more history repeated itself and another military coup led by General Umar al-Bashir installed the National Islamic Front in 1989. The new government's commitment to the Islamic cause intensified the north-south conflict. Meanwhile, the period of the 1990s saw a growing sense of alienation in the western and eastern regions of Sudan from the Arab center. The rulers in Khartoum were seen as less and less responsive to the concerns and grievances of both Muslim and non-Muslim populations across the country. Alienation from the "Arab" center caused various groups to grow sympathetic to the southern rebels led by the Sudan People's Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A), and in some cases, prompted them to flight alongside it.

The Bashir government combined internal political repression with international Islamist activism. It supported radical Islamist groups in Algeria and supported Iraq's invasion of Kuwait. Khartoum was established as a base for militant Islamist groups: radical movements and terrorist organizations like Osama Bin Laden's al Qaida were provided a safe haven and logistical aid in return for financial support. In 1996, the U.N. imposed sanctions on Sudan for alleged connections to the assassination attempt on Egyptian President Mubarak. Its policy toward the south was to pursue the war against the rebels while trying to manipulate them by highlighting tribal divisions. Ultimately, this policy resulted in the rebels' uniting under the leadership of Colonel John Garang. During this period, the rebels also enjoyed support from Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Uganda. The Bashir government's "Pan-Islamic" foreign policy, which provided support for neighboring radical Islamist groups, was partly responsible for this support for the rebels. The 1990s saw a succession of regional efforts to broker an end to the Sudanese civil war. Beginning in 1993, the leaders of Eritrea, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Kenya pursued a peace initiative for the Sudan under the auspices of the Intergovernmental Authority for Development (IGAD), but results were mixed. Despite that record, the IGAD initiative promulgated the 1994 Declaration of Principles (DOP) that aimed to identify the essential elements necessary to a just and comprehensive peace settlement; i.e., the relationship between religion and the state, power sharing, wealth sharing, and the right of self-determination for the south. The Sudanese Government did not sign the DOP until 1997 after major battlefield losses to the SPLA. That year, the Khartoum government signed a series of agreements with rebel factions under the banner of "Peace from Within." These included the Khartoum, Nuba Mountains, and Fashoda Agreements that ended military conflict between the government and significant rebel factions. Many of those leaders then moved to Khartoum where they assumed marginal roles in the central government or collaborated with the government in military engagements against the SPLA. These three agreements paralleled the terms and conditions of the IGAD agreement, calling for a degree of autonomy for the south and the right of self-determination. However, by mid-2001, prospects for peace in Sudan appeared fairly remote. A few days before the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in New York and Washington, the Bush Administration named former Senator John Danforth as its Presidential Envoy for Peace in the Sudan. His role was to explore the prospects that the U.S. could play a useful role in the search for a just end to the civil war, and enhance the delivery of humanitarian aid to reduce the suffering of the Sudanese people stemming from the effects of civil war. The terrorist attacks of September 11 dramatically impacted the bilateral relationship between the United States and the Khartoum government. (For "U.S.-Sudanese Relations," see below.)

End to the Civil War

In July 2002, the Government of Sudan and the SPLM/A reached a historic agreement on the role of state and religion and the right of southern Sudan to self-determination. This agreement, known as the Machakos Protocol and named after the town in Kenya where the peace talks were held, concluded the first round of talks sponsored by the IGAD. The effort was mediated by retired Kenyan General Lazaro Sumbeiywo. Peace talks resumed and continued during 2003, with discussions regarding wealth sharing and three contested areas. On November 19, 2004, the Government of Sudan and the SPLM/A signed a declaration committing themselves to conclude a final comprehensive peace agreement by December 31, 2004, in the context of an extraordinary session of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) in Nairobi, Kenya--only the fifth time the Council has met outside of New York since its founding. At this session, the UNSC unanimously adopted Resolution 1574, which welcomed the commitment of the government and the SPLM/A to achieve agreement by the end of 2004, and underscored the international community's intention to assist the Sudanese people and support implementation of the comprehensive peace agreement. It also demanded that the Government of Sudan and the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) halt all violence in Darfur. In keeping with their commitment to the UNSC, the Government of Sudan and the SPLM/A initialed the final elements of the comprehensive agreement on December 31, 2004. The two parties formally signed the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) on January 9, 2005. The U.S. and the international community have welcomed this decisive step forward for peace in Sudan.

Comprehensive Peace Agreement

The CPA established a new Government of National Unity and the interim Government of Southern Sudan and called for wealth-sharing, power-sharing, and security arrangements between the two parties. The historic agreement provides for a ceasefire, withdrawal of troops from southern Sudan, and the repatriation and resettlement of refugees. It also stipulates that by the end of the six-year interim period, during which the various provisions of the CPA are implemented, there will be elections at all levels, including for president, state governors, and national and state legislatures.

On July 9, 2005, the Presidency was inaugurated with al-Bashir sworn in as President and John Garang, SPLM leader, installed as First Vice President. Ratification of the Interim National Constitution followed. The Constitution declares Sudan to be a "democratic, decentralized, multi-cultural, multi-ethnic, multi-religious, and multi-lingual State."

On July 30, 2005, the charismatic and revered SPLM leader John Garang died in a helicopter crash. The SPLM immediately named Salva Kiir, Garang' s deputy, as First Vice President. As stipulated in the CPA, Kiir now holds the posts of President of the Government of Southern Sudan and Commander-in-Chief of the SPLA.

Implemented provisions of the CPA include the formation of the National Legislature, appointment of Cabinet members, establishment of the Government of Southern Sudan and the signing of the Southern Sudan Constitution, and the appointment of state governors and adoption of state constitutions.

New CPA-mandated commissions have also been created. Thus far, those formed include the Assessment and Evaluation Commission, National Petroleum Commission, Fiscal and Financial Allocation and Monitoring Commission, and the North-South Border Commission. The Ceasefire Political Commission, Joint Defense Board, and Ceasefire Joint Military Committee were also established as part of the security arrangements of the CPA.

With the establishment of the National Population Census Council, plans are anticipated for a population census to be conducted in February 2008 in preparation for national elections in 2009. The CPA mandates that the government hold a referendum at the end of a six-year interim period in 2011, allowing southerners to secede if they so wish. On January 9, 2007, commemoration of the second anniversary of the CPA was held in Juba. During the ceremony, President Bashir and First Vice President Kiir exchanged forceful accusations concerning the delays in the implementation of the agreement. In his remarks, Salva Kiir described the achievement of the CPA as the most important achievement in modern Sudanese history and confirmed that there would be no retreat from the path of peace.

While some progress has been achieved during the last two years, meaningful implementation of key CPA requirements has faltered and relations between the National Congress Party (NCP) and SPLM are at an all-time low. As of October 2007, a lack of progress on issues such as north-south border demarcation, certain security provisions, and north-south sharing of oil revenues threatened to erode the CPA. International attention is refocusing on the CPA as the mainstay of peace in Sudan in response to calls for reinvigorated CPA implementation.

Darfur

In 2003, while the historic north-south conflict was on its way to resolution, increasing reports of attacks on civilians, especially aimed at non-Arab tribes, began to surface. A rebellion broke out in Darfur, in the extremely marginalized western Sudan, led by two rebel groups--the SLM/A and the JEM. These groups represented agrarian farmers who are mostly non-Arabized black African Muslims. In seeking to defeat the rebel movements, the Government of Sudan increased arms and support to local tribal and other militias, which have come to be known as the "Janjaweed." Their members were composed mostly of Arabized black African Muslims who herded cattle, camels, and other livestock. Attacks on the civilian population by the Janjaweed, often with the direct support of Government of Sudan forces, have led to the death of tens of thousands of persons in Darfur, with an estimated 2.0 million internally displaced persons and another 234,000 refugees in neighboring Chad.

On September 9, 2004, Secretary of State Colin L. Powell told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, "genocide has been committed in Darfur and that the Government of Sudan and the Janjaweed bear responsibility--and that genocide may still be occurring." President Bush echoed this in July 2005, when he stated that the situation in Darfur was "clearly genocide."

A cease-fire between the parties was signed in N'Djamena, Chad, on April 8, 2004. However, despite the deployment of an African Union Military Mission to monitor implementation of the cease-fire and investigate violations, violence has continued. The SLM/A and JEM negotiated with the Government of Sudan under African Union auspices, resulting in additional protocols addressing the humanitarian and security aspects of the conflict on November 9, 2004. Like previous agreements, however, these were violated by both sides. Talks resumed in Abuja on June 10, 2005, resulting in a July 6 signing of a Declaration of Principles. Further talks were held in the fall and early winter of 2005 and covered power sharing, wealth sharing, and security arrangements. These negotiations were complicated by a split in SLM/A leadership.

The African Union, with the support of the UNSC, the U.S., and the rest of the international community, began deploying a larger monitoring and observer force in October 2004. The UNSC had passed three resolutions (1556, 1564, and 1574), all intended to move the Government of Sudan to rein in the Janjaweed, protect the civilian population and humanitarian participants, seek avenues toward a political settlement to the humanitarian and political crisis, and recognize the need for the rapid deployment of an expanded African Union mission in Darfur. The U.S. has been a leader in pressing for strong international action by the United Nations and its agencies.

A series of UNSC resolutions in late March 2005 underscored the concerns of the international community regarding Sudan's continuing conflicts. Resolution 1590 established the UN Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) for an initial period of six months and decided that UNMIS would consist of up to 10,000 military personnel and up to 715 civilian police personnel. It requested UNMIS to coordinate with the African Union Mission in Sudan (AMIS) to foster peace in Darfur, support implementation of the CPA, facilitate the voluntary return of refugees and internally displaced persons, provide humanitarian demining assistance, and protect human rights. The resolution also called on the Government of Sudan and rebel groups to resume the Abuja talks and support a peaceful settlement to the conflict in Darfur, including ensuring safe access for peacekeeping and humanitarian operations.

Resolution 1591 criticized the Government of Sudan and rebels in Darfur for having failed to comply with several previous UNSC resolutions, for ceasefire violations, and for human rights abuses. The resolution also called on all parties to resume the Abuja talks and to support a peaceful settlement to the conflict in Darfur; it also forms a monitoring committee charged with enforcing a travel ban and asset freeze of those determined to impede the peace process, or violate human rights. Additionally, the resolution demanded that the Government of Sudan cease conducting offensive military flights in and over the Darfur region. Finally, Resolution 1593 referred the situation in Darfur to the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (ICC) and called on the Government of Sudan and all other parties to the conflict in Darfur to cooperate with the ICC.

On May 5, 2006, under strong pressure from the African Union (AU) and the international community, the government and an SLM/A faction led by Minni Minawi signed the Darfur Peace Agreement (DPA) in Abuja. Unfortunately, the conflict in Darfur intensified shortly thereafter, led by rebel groups who refused to sign. In late August government forces began a major offensive on rebel areas in Northern Darfur. On August 30, the Security Council adopted UNSCR 1706, authorizing the transition of AMIS to a larger more robust UN peacekeeping operation. To further facilitate an end to the conflict in Darfur, President Bush announced the appointment of Andrew S. Natsios as the Special Envoy for Sudan on September 19, 2006.

In an effort to resolve Sudan's opposition to a UN force, UN Secretary General Kofi Annan and African Union Commission Chair Alpha Oumar Konare convened a meeting of key international officials and representatives of several African and Arab states in Addis Ababa on November 16, 2006. The agreement reached with the Government of Sudan provided for UN support to AMIS in three phases--light, heavy, and a joint AU/UN hybrid support operation. On November 30, the African Union Peace and Security Council also endorsed the Addis Ababa conclusions.

International efforts in 2007 focused on rallying support for DPA signatory and non-signatory rebel movements for renewed peace talks, and on finalizing plans for the joint AU/UN hybrid operation. UN Security Council Resolution 1769 was adopted on 31 July, providing the mandate for a joint AU/UN hybrid force to deploy to Darfur with troop contributions from African countries. The UN African Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) is to assume authority from AMIS in the field no later than December 31, 2007.

Following the passage of UNSCR 1769, a conference was held August 3-5, 2007 in Arusha, Tanzania between key UN and AU officials and delegates from Darfur rebel groups. Many movements' political and military leaderships were brought into the discussion in preparation for earnest peace talks. Peace talks between the Government of Sudan and rebel factions are scheduled to take place in Tripoli, Libya on October 27, 2007.

References

- Ojibwa, Ancient Egypt: Nubian Kush Conquers Egypt, DailyKos

- University of Chicago, The History of Ancient Nubia